Nonetheless,

it has remained an icon of Winnipeg's skyline for a century. it has

outlasted all but two other bridges and has seen THREE incarnations of

its nearest neighbour, the Salter Street / Slaw Rebchuck Bridge.

This

is a five part series on the history of Winnipeg's Arlington Street

Bridge to commemorate the centenary of its opening on February 5, 1912.

Part 1: Spanning the Tracks

Part 2: Construction and Controversy

Part 3: The Bridge as "bugbear"

Part 4: What about the Nile River connection

Part 5: The Future of the Arlington Street Bridge

2023 UPDATE: End of the line for the Arlington Bridge?

Part 2: Construction and Controversy

Part 3: The Bridge as "bugbear"

Part 4: What about the Nile River connection

Part 5: The Future of the Arlington Street Bridge

2023 UPDATE: End of the line for the Arlington Bridge?

Part 1: Spanning the Tracks

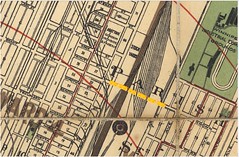

Main Street Subway ca. 1908, (Peel's Prairie Provinces)

When the first CPR train pulled into Winnipeg in August 1882 it meant instant traffic mayhem for Winnipeggers.

To cross the tracks by foot, cart, or streetcar, the only option was a grade crossing at Main Street*. Initially, there were four tracks to contend with but that number doubled to eight in 1900. Newspaper stories of the day mention waits as long as twenty minutes for the trains to clear and allow street traffic to flow.

(* There was a grade crossing at McPhillips Street, but at the time this was bald prairie at the western boundary of the city. There was little street traffic and certainly no streetcars there.)

Some relief came in 1899 when the first Salter Street bridge was constructed. It was a wooden structure that was a thousand feet long and seventeen feet wide that could only handle carts and pedestrians.

In 1904, a subway at Main Street and a smaller one at Annabella Street were constructed. This finally allowed traffic to cross to and from the North End regardless of train traffic but the city and its traffic volume had grown so much since 1882 that both the city and streetcar company were desperate to find additional routes.

A plan was released in 1906 for something called the Central Belt Line. This would be a second north-south streetcar route that would run from the city's northern boundary with West Kildonan, south along Brown, Brant, and Arlington streets, cross the Assiniboine River and continue into Fort Rouge.

The proposal called for the construction of two spans. The Arlington Street Bridge would join the south end of Arlington Street in Wolseley to Harrow Street in Fort Rouge, and the Brown and Brant Streets Overpass would cross the CPR yards between Logan and Dufferin avenues.

While this new belt line would help solve the city's traffic and connectivity problems, some felt that it was located too far west and preferred that the Salter Street Bridge be replaced with a modern structure able to handle streetcars.

The Central Belt Line proposal, and the Brown and Brant Streets Overpass in particular, would likely have never come to pass if it wasn't for a man named Archibald A. McArthur.

McArthur was born and raised in Ontario. He was a farmer and award winning cattle breeder who took numerous top Dominion and North American honours for his stock. In 1881, he came to Manitoba to "spy out the land", (the term used in his obituary), and the following year moved his family out here and started a grocery store in Winnipeg.

McArthur and his family then moved to Gull Lake, Saskatchewan to return to farming from 1888 to 1891 before returning to Winnipeg and opening McArthur Grocery at 728 Logan Avenue (at Lulu Street - now demolished).

A. A. McArthur. (Source)

McArthur first ran for Winnipeg city council in 1904 and lost. He was elected the following year, (municipal elections were an annual thing back then), and served for three one-year terms.

By 1906, McArthur was chair of city council's bridge committee and the man tasked with negotiating road and land improvements between the city and the C.P.R.. The Brown and Brant Streets Overpass was debated and approved by his committee, made it through a council vote, and became part of the agenda of the City of Winnipeg / C.P.R. improvements negotiations for the following year.

The C.P.R. dragged its heels in the negotiations and opted to let the Railway Commission in Ottawa rule as to whether or not it had to cost share the Brown and Brant Streets Overpass with the city. The reply came in November 1907 that they did not have to contribute a cent to it.

C.P.R. Tracks ca. unknown. (Source)

Even without a cost-sharing partner, McArthur ensured that the project moved ahead. He touted to his colleagues on city council the benefits of the larger Central Belt Line plan to help keep the overpass alive.

(It is unclear why McArthur was so passionate about the Brown and Brant Streets Overpass. As a small grocery store owner, there was little direct benefit to him. He was, however, a strong believer in the city and in big infrastructure projects. He also pushed for a central drinking water supply for the city, which ended up being the aqueduct, and for a power generating station at Point du Bois.)

McArthur convinced his colleagues to allow a $600,000 money by-law be put to voters in the December 1907 municipal election. This figure included the expansions of the Main Street and Louise bridges as well as $240,000 for the much less popular Brown and Brant Streets Overpass.

Ratepayers were not in a spending mood. Aside from school construction, no infrastructure bylaws had been approved since the end of 1905. This time out it would be no different. On December 10, 1907, the bridge bylaw was narrowly defeated by a vote of 1484 for and 1585 against. The city tried again in the December 1908 election with similar results.

In that 1908 election, McArthur gave up his council seat and won a seat on the city's Board of Control, a sort of elected finance committee that sat separately from city council. As a controller, McArthur could likely keep a better eye on the overpass and other infrastructure projects he supported.

June 24, 1909. Manitoba Free Press.

On June 24, 1909, the same $600,000 bridge bylaw was put before the voters for the third time. The Free Press, which had always been a proponent of the Brown and Brant Streets Overpass, wrote in an editorial on the day of the vote: "Another improvement needed by a very large body of the city's population is a bridge over the Canadian Pacific Railway tracks farther west than the present overhead bridge at Salter Street".

The third time was a charm for the bylaw as it finally won. The Free Press speculated the following week that the new overpass was still going to face a stiff fight on council if it was going to see the light of day: Controller McArthur Is likely to have trouble of his own In bringing about the speedy materialization of this overhead bridge project for there Is a strong element In the council, which, while acquiescing to the mandate of the ratepayers as expressed by the recent vote sees no need for haste in expending the $232,000 required to erect the structure. (July 8, 1909, Manitoba Free Press.)

Aldermen Gowler and Willoughby were the main detractors of the project on council and continued to speak out against it. A fellow member of the board of control, Controller Harvey, publicly stated that the other improvements voted for in the various winning money bylaws should be given precedence, adding: "...but if Controller McArthur thinks that sidewalks, roads and sewers should be laid over to give this bridge preference he is entitled to think so." (January 27, 1910, Manitoba Free Press).

It turns out that even while the overpass project was being rejected at the polls, McArthur was doing his homework.

Shortly after the winning vote, he was able to produce detailed plans for the bridge that had already been submitted and approved by the Railway Commission in Ottawa!

Within a month, a bylaw to expropriate the necessary land to bring Brown Street up to the edge of the tracks was tabled and passed at council.

The Brown and Brant Streets Overpass was going full steam ahead.

See Part 2: Construction and Controversy

Further writing by me:

Moving the CP Yards, the early years West End Dumplings (2012)

The process to replace the Arlington Bridge has begun West End Dumplings (2014)

Bridging the Past Winnipeg Free Press 2015

Has the Arlington Bridge dodged another bullet? West End Dumplings (2020)

Arlington Street's great lengths Winnipeg Free Press (2022)

How many lanes does Arlington Street Have? West End Dumplings (2021)

My Flickr photo album of the Arlington Bridge

4 comments:

Thank you. Not only was your article informative, but it brought my Great Great Grandfather Archibald A McArthur to life for me.

You quoted his obituary. I have been searching for a copy for a long time. If you have any suggestions as to where I might look I would again be grateful.

Oh wow, great to hear from you ! The bridge really should have been named for him !

When I get home I will send you the obit(s) and any other personal articles I found about him from the Tribune and Free Press archives. If you want to send me an email address that I can reply to at cassidy at mts.net.

Was Arlington Street named after the bridge? Who was "Arlington"?

Arlington was the name of the street from the Assiniboine River to Notre Dame. When the full stretch of road, including Brown and Brant Streets to the north, were renamed a single "Arlington Street", the Brown and Brant Street Bridge took the new name.

As for who Arlington is, I could not find an attribution in the usual "History of Winnipeg Street Names" sources. Arlington is, however, an old location name in Britain. one possibility is after Arlington in Devon: http://www.britainexpress.com/counties/devon/houses/Arlington-Court.htm

Post a Comment