On October 3, 1918, two soldiers at the I.O.D.E Convalescence Home in Winnipeg die of Spanish Influenza. they are the first known cases in Manitoba. The moment that the city and province had been dreading was now here.

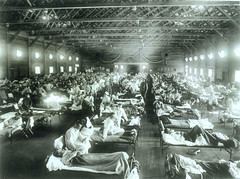

Camp Funston, Kansas during "Spanish" Flu Outbreak (source)

The “Spanish” flu wasn’t Spanish at all. Many believe that the first recorded case occurred on March 11, 1918 at a military camp in Fort Riley, Kansas. A soldier reported flu-like symptoms that morning and by lunchtime another 100 had fallen ill (PBS). By the end of their training camp over 1,000 soldiers were ill and 46 had died (Duncan).

The “Spanish” flu wasn’t Spanish at all. Many believe that the first recorded case occurred on March 11, 1918 at a military camp in Fort Riley, Kansas. A soldier reported flu-like symptoms that morning and by lunchtime another 100 had fallen ill (PBS). By the end of their training camp over 1,000 soldiers were ill and 46 had died (Duncan).

In the days to follow, more cases were reported in the Eastern U.S. as well as in parts of France and Spain. It was the Spanish media, not restricted by wartime reporting embargoes, that first raised a red flag about the illness, thus earning it the nickname "Spanish Flu" or "The Spanish Lady" (Humphries).

Influenza was well known around the world, but this strain was unique.

For one, it struck down the healthiest people in society - those in the 15 to 35 age group. This was the same demographic that was traveling the globe in large numbers during the War.

The strain was also incredibly deadly. Recent studies suggest that it was 39,000 times more virulent than common flu. The resulting death was not pretty: “Men literally choked to death with pulmonary (swelling), the lungs so swamped with blood, foam and mucous that the faces were grey and the lips purple” (Duncan).

The Spanish Flu struck the world in three waves. The first, as mentioned above, came in Spring 1918. The range was believed to be limited to select parts of the U.S. and Europe and the death rate for those infected was relatively low. A second wave in Autumn 1918 went global and was much more virulent than the first. A third and final wave came in the Winter of 1918 -19 that was as deadly as the second, but less widespread.

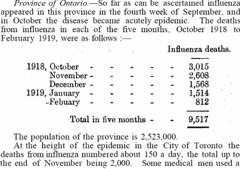

Ontario Deaths from Spanish Flu and complications 1918-19 (source)

The flu is thought to have arrived in Canada in late summer 1918, likely brought to Eastern Canada by US soldiers en route to the front. Quebec was hit particularly hard in September. It eventually spread westward with the movement of troops back to their home towns (Humphries).

Between October 9 and November 2, 1918, there were 1,682 influenza deaths in Toronto. In Montreal influenza infected as many as 1,000 new people per day in October. Due to the sheer numbers of dead, hotels were converted to morgues and streetcars were modified to be used as hearses. (Sulivan, Humphries).

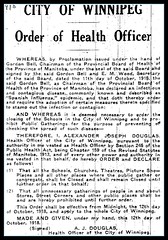

Above: Winnipeg Tribune, September 30, 1918

Manitoba's first taste of the new train of influenza was a controlled one. On September 30, 1918, it was announced that a troop train with 15 stretcher-bound cases aboard would arrive in the city that night. By the time it arrived there were 23 cases.The solders were from Quebec heading west for deployment to Siberia and all were healthy when they were last checked at Fort William (Thunder Bay). They were taken to the IODE Convalescent Soldiers' Home in Winnipeg which was immediately quarantined.

On October 3, 1918, two of the solders, Privates E. Murray and W. Barney, died. They were Quebecois, but they were the first two Spanish Flu deaths in Manitoba. Public health officials had to admit that it was almost a certainty that the disease was now loose in the community at large.

Free Press carriers in masks, ca 1918

For Manitoba, the timing could not have been worse. The war was already taking a heavy toll on the population of men from the very age group that the influenza targeted. Many prairie towns feared that between the two they could lose most of a generation.

Despite months of media coverage about flu deaths from around the world, the military and local public health officials butted heads a number of times in early October over the fact that soldiers who may have come into contact with the disease and were told to stay at home, even those officially quarantined, were regularly brought out from their beds and homes for movie nights and other day trips in the community. (Jones).

The disease moved slowly and had a low mortality rate at first. A third Quebec soldier died on October 9th. There were cases reported among local soldiers, but they were mild and most were quarantined at home. On October 11th, however, the King George Hospital admitted the first patient too ill to be quarantined at home (Jones). As suspected, the flu was in the community at-large.

Winnipeg Free Press, October 12, 1918

On October 12, 1918 Gordon Bell, chair of the Provincial Public Health Board declared an emergency and decreed that effective midnight all schools, cinemas, church services and other such gathering places would be shut in Winnipeg and its suburbs until further notice. Soon after the restrictions were province-wide.

A. J. Douglas, Winnipeg's Health Officer, released an order of his own. It covered all of what Bell prescribed with a few additions. In Winnipeg you would be fined $50 if caught spitting in the street and it was illegal for the public to approach a train in a station. (Other jurisdictions had their own twists; for instance in Alberta municipalities it was illegal to be in public without wearing a cotton mask which created one of the most iconic images of Canada's influenza fight.)

November 15, 1918, Manitoba Free Press

Despite its slow start, within a couple of weeks Winnipeg's public health system was overwhelmed by influenza. By October 31 there had been 1,910 cases in Winnipeg and 66 deaths.

A big problem faced by Winnipeg's public health officials was that rather than go to hospital, (for civilians it was the King George Isolation Hospital or a special emergency room set up on Logan Avenue), many of the sick preferred to stay at home. This put a strain on doctors and nurses and at times entire hospital wards had to be left unattended as staff were dispatched into the field.

The city's relief committee and charitable organizations had to ramp up their services as thousands found themselves jobless, either due to illness of the closure of public places.

By the end of November 1918, Winnipeg had faced 9,031 reported influenza cases with 526 deaths, about 10 per day, before the numbers began to ease off and the public health order was rescinded on November 27, 1918. (See below for the statistics.)

In December the number was 2,859 infected with 197 dead. In the final month of the outbreak, January 1919, there were 973 cases with 101 deaths. (Britain p 277).

It turned out that of the approximately 825 victims, 60 per cent were between the ages of 20 to 39. (Jones).

November 28, 1918, Winnipeg Tribune

Outside the city, the disease was slow to take hold. By October 30th Portage La Prairie had 118 cases and no deaths while Brandon had 187 cases and five deaths.

The hardest hit region of the entire province was Northern Manitoba in January and February 1919. A special dispatch on the front page of the Manitoba Free Press of February 6, 1919 told of of a health emergency being declared in the north:

“Three weeks ago the Indians were free of the scourge, according to the reports brought in. The dog mushers say that the epidemic has taken 107 at Norway House, 125 at

Cross Lake, 20 at Red Earth and it is taking a heavy toll at Pelican Narrows. At this place, in one house 20 Indians were lying on the floor sick with four dead bodies in

amongst them. All were too ill to remove the dead.”

In a period of just 6 weeks Norway House lost almost 20% of their population, 183 of 1000 people, due to influenza (Herring).

Global death counts numbers initially ranged from 20 - 40 million dead, though today that is believed to be closer to 50 million with some estimating it as high as 100 million (Taubenberger). Canada's total death toll was 50,000 (Duncan), the U.S. lost 675,000 (PBS), and India 5 million (Duncan).

Winnipeg Influenza Statistics to November 28, 1918:

November 28, 1918, Winnipeg Tribune

Some Notable Manitoba Flu Deaths:

For more on Alan McLeod V.C.. For more on Joe Hall

Sources referenced above by name:

Duncan, K., Lessons from the 1918 Spanish Flu, 2006.

PBS Online, American Experience - Influenza 1918

Duncan, K., Lessons from the 1918 Spanish Flu, 2006.

British Ministry of Health, Reports on Public Health and Medical Subjects No.4, 1920.

From: FluWeb Influenza Historical Resources Database, hosted by the School of Population Health, University of Melbourne, Australia.

Herring, Ann D., There Were Young People and Old People and Babies Dying Every Week: The 1918-1919 Influenza Pandemic at Norway House, Ethnohistory, Vol. 41, No. 1 (Winter, 1993), pp. 73-105, Duke University Press.

Humphries, Mark Osborne, The Horror at Home: The Canadian Military and the "Great" Influenza Pandemic if 1918, 2005.

Jones, Esyllt W., Infuenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg,University of Toronto Press, 2007.

MHS Influenza, Manitoba History, Number 23, Spring 1992.

PBS Online, American Experience - Influenza 1918

Taubenberger JK, Morens DM. 1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics, Emerg Infect Dis. 2006 Jan.

More ‘Spanish' Flu Resources:

Recent Media:

In 1918 Flu Outbreak, a Cool Head Prevailed

The New York Times, April 30, 2009

When Half The City Took Ill

Toronto Star, May 2, 2009

More ‘Spanish' Flu Resources:

For the Winnipeg experience you should check out Jones' Infuenza 1918: Disease, Death, and Struggle in Winnipeg. Not just stats and a great commentary on how the epidemic played out , it also looks at the personal lives and struggles of average Winnipeggers at the time and how it would impact the city far beyond just those three months. (To hear a podcast of an interview with the author.)

CBC Archives past radio and tv reports: Influenza: Battling The Last Great Virus

PBS' American Experience page. Timelines, stories, interviews, etc. A really good resource.

The Centers for Disease Control have a new site to mark the 90th anniversary called The Pandemic Influenza Storybook featuring photos and recollections of those that lived through it.

November 4, 1918, Winnipeg Tribune

Recent Media:

In 1918 Flu Outbreak, a Cool Head Prevailed

The New York Times, April 30, 2009

When Half The City Took Ill

Toronto Star, May 2, 2009

Canadian Press September 15, 2008

Helen Branswell, Canadian Press September 16, 2008

Ian Sample, The Guardian Weekly (UK) 10 October 2005

Stefan Lovgren, National Geographic News, February 5, 2004

CanWest News Service, November 10, 2005

No comments:

Post a Comment